The Lost Coast Trail

A Hiker's Guide to California's Hidden Coast

Hiking the Lost Cost Trail - Introduction

The Lost Coast is a stretch of California coastline so rugged that roads have not conquered it. The remoteness is a rare respite from the rest of the state. There are no mansions tucked along hillsides or congested lines of traffic winding along the cliffs. Here crumbling gashes of the King Range tower from the sea, blocking the way of everyone not on foot.

Between the cliffs and the sea, the Lost Coast Trail passes along the narrow band of tortured beach. It is the domain of the hiker, a desolate and severe landscape draped by a pristine ecosystem. The path leads from hidden beaches to expansive vistas at dizzying heights above the surf. Apart from sea lions and the occasional troop of Scouts, hikers discover pure solitude. The Lost Coast Trail is one of the finest beach backpacking trips found in the United States, and it has steadily grown in fame and popularity over the years.

Often the trail is no more than a foreboding band of beach that vanishes into an oblivion of marine fog. Twice per day, there is no Lost Coast Trail. Stretches of the route vanish under the high tide, replaced by surf pounding against the cliffs.

Location

The King Range National Conservation Area in Northern California (Google Maps)Trailheads

Mattole BeachBlack Sands Beach near Shelter Cove

When to go

Late May through early October usually has the best weather.Reservations

Overnight camping reservations are required from recreation.govBear canisters

All hikers are required to carry at least one approved bear canister per person.Map

Printable map (download)Trip Length

24.6 miles (39.6 km)Time to hike

3-4 daysDifficulty

Challenging for most hikers due to the rough beach terrain.Dogs allowed?

Dogs are allowed but the BLM advises against bringing them due to the paw-destroying sand and gravel.Hazards

Intertidal-zone hiking, sneaker waves, wind exposure, poison oak (abundant), creek crossings (no bridges, some may be impassible after storms), rattlesnakes (infrequent), black bears.Important Phone numbers

BLM Arcata Field Office: (707) 825-2300King Range Field Office: (707) 986-5400

Location

The Lost Coast Trail skirts the coast of the King Range National Conservation Area. This is the western edge of Humboldt County in Northern California. To the south of the King Range, Highway 1 veers eastward, blocked by impassible slopes near Rockport. If you were to fly a plane up the coast from here, the next coastal highway you would spot is at Ferndale, roughly 90 miles north. Between lies the longest stretch of undeveloped US Pacific coastline outside of Alaska.

Planning a backpacking trip on the Lost Coast Trail

Trip Length

There are two official portions of the Lost Coast Trail. Most people (and this guide) are only interested in the northern section. Most of the time when someone says "Lost Coast Trail," they are referring to just the northern section. This trail runs 24.6 miles (39.6 km) between Mattole and Black Sands Beach near Shelter Cove.

The southern Lost Coast Trail continues further into Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, eventually reaching Usal Beach, about 32 miles from Black Sands Beach. The sheer cliffs of the next stretch of coast are inaccessible by foot, so the trail begins inland several miles east from Shelter Cove, and doesn't return to the coast until near Needle Rock. Sinkyone State Park has tighter regulations than the BLM. Dogs are not allowed and camping must be within designated areas. The southern Lost Coast Trail rarely touches the beach, staying inland and skirting the tops of the bluffs most of the way. It is a beautiful hike, but it is not top-shelf like the northern section.

This guide refers only to the northern Lost Coast Trail. This is the section between Mattole Beach and Black Sands Beach (Shelter Cove).

When to go

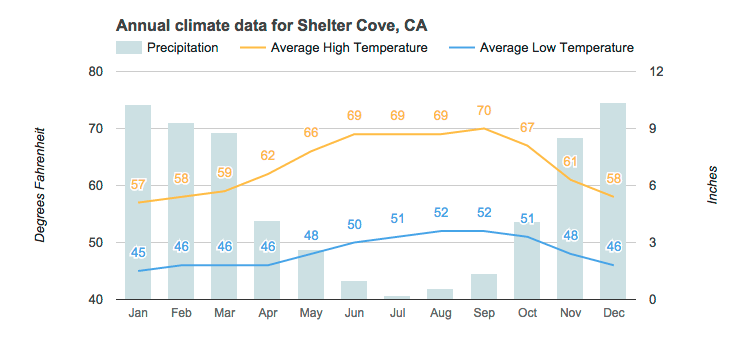

The nicest time of year to hike the Lost Coast Trail is usually from late May to early October. The Pacific Ocean buffers coastal temperatures to comfortable levels for most of the year.

Lows rarely drop down to freezing in the winter. Rain is the biggest concern in the off-season. From late October to April the Lost Coast can see sixty or more inches of rain. Many of the streams on this route become engorged and are difficult to cross after heavy rains.

Besides rain, the wind can be incessant and harsh. You should bring a full Gore-Tex rainsuit, and not rely on ponchos or umbrellas for this trip.

Off-season hikingA stretch of good weather can make hiking the Lost Coast Trail reasonable in the off-season. Always check trail conditions with the BLM before leaving. Prepare for larger surf and the possibility of getting wet. Keep a change of clothes in a dry bag and be vigilant to treat symptoms of hypothermia in yourself or others.

Intertidal Zone Hiking

This is serious business! There are three stretches of trail that are impassible at high tide. Two are around 4 miles in length. If you get caught in one of these zones by an incoming tide, you might die.

Planning your hike around the tides is necessary. About 9.5 miles (15.3 km) of the 24.6 mile (39.6 km) route north of Shelter Cove is inaccessible at high tide. Depending on your agility, "impassible" can mean seas above the +1.5 ft to +3 ft tide range. This assumes calm seas. Always take weather off the coast into consideration when planning your day. Large breakers make some sections hazardous even at low tide. Use extra care if there is a small craft advisory in effect offshore.

In general, the lower the tide gets, the easier passage will be. In some places the low tide exposes packed wet sand. When it does, walking comes easier here, and you might be able to travel at two or three times the speed one can rock-hop further up the beach. As a starting estimate when planning your itinerary, know that the average hiker covers about 1.5 miles per hour along the beaches.

Hike Difficulty

The Lost Cost Trail is strenuous. It is best attempted when you are in good physical shape. Given the physical challenge plus the dangers of the waves, it is not a good hike for young children. All but the sturdiest of dogs will experience something between hardship and injury.

I can't recommend this trail for people who have never backpacked. If you are considering this for your first backpacking trip, you might be happier if you go for an easy overnighter somewhere safer first (i.e. no intertidal zone hiking, reserve the possibility of turning back). This gives you an opportunity to test your gear and make sure you've got everything you need. Most importantly it will let you see if you are physically and mentally prepared for the hardships of backpacking. The same applies for any friends you might bring along, especially if you're leading a group of inexperienced hikers. Nothing ruins a good backpacking trip like a hysterical hiking companion.

The old creaky knees

This is not the best walk for people with knee or joint problems. Hiking poles can help you to avoid falls, strains and sprains on the unstable rocks. On this note, most people appreciate keeping their pack weight down due to the unstable walking surfaces. If you have the ability to go ultralight, this is the trip to do it.

It's the walking surfaces that make the trail so difficult. After a few hours of travel, the hiker will look upon any patch of firm ground with relief. For most of the way, a footstep is rarely steady. There are stretches of deep sand that bury each step. There are rocks the size of large grains of rice that do the same. Other beaches are strewn with heaps of marble-sized rocks. These warp each stride as they roll underfoot. There are many more miles of boulders. They are just small enough to shift and roll under the weight of a man. This flexes knees and ankles in ways they should not bend.

Jagged points of bedrock protrude into the sea and divide stretches of beach. Around these points travelers must scramble along slippery ledges during short windows of low tide. It is not all hard travel though. Glorious firm trail winds through the coastal meadows of Spanish and Miller Flat, and it's not surprising that this marks the highlight of the trip for many hikers.

Trail running

The Lost Coast Trail is not a good route for trail runners. The exception is the stretch of trail between Miller Flat and the north end of Big Flat. Spanish Flat is also a fine place to run. If you have time to kill at Big Flat, the inland trail through the prairie makes for a gorgeous running route.

Dogs on the Lost Coast Trail

The BLM allows dogs on the Lost Coast Trail but recommends against taking them.

Most dogs end up having a rough time. It's a poor idea to bring your dog unless it is a seasoned hiker. Be aware that the sand acts like sand paper and and rubs the pads and the skin between the pads raw. Jumping from boulder to boulder can bruise nails to the point of bleeding. It is imperative to bring dog boots in case of trouble. Your dog will be most comfortable if it wears them the entire trip. If your dog is too playful at the start of the day, consider using a leash so it does not prematurely exhaust itself.

Hiking one-way and transportation between trailheads of the Lost Coast Trail

Many people prefer to hike the Lost Coast Trail one-way over three days. Swapping keys with another party hiking the other direction works great for this. Another option for hiking one-way is to book a trip with one of the BLM-approved private shuttle services.

Even though Mattole and Shelter Cove are 25 miles apart on the coast, the drive is 50 miles, and takes about two hours. The miles out here don't come easy. There’s no public transportation.

Currently two carriers offer transport from Shelter Cove to Mattole, but not the other direction. Taking the shuttle before your hike means you don’t have to worry about being on time to meet a shuttle at the end of your hike. The drive takes several hours along the mountain roads and costs start around $200. The shuttle services can be booked solid months in advance, so plan ahead.

On the Lost Coast, the wind often blows from the northwest. The harder it blows, the more people appreciate hiking the Lost Coast Trail southbound.

Round trip, or partial trips on the Lost Coast Trail

If you need to start and end your trip at the same trailhead, you have a few options. You can do the entire trip in five or six days. For a shorter trip, Big Flat is a popular destination and is one of the more memorable sites along the Lost Coast Trail. You could do a four day round-trip from Mattole to Big Flat, or overnight from Shelter Cove. While opinions vary, the stretch of trail between Randall Creek and Big Flat stands out as stellar for its abundance of coastal prairie.

- Mattole River: N 40° 17.335' W 124° 21.383'

- Windy Point: N 40° 16.257' W 124° 21.77'

- Punta Gorda: N 40° 14.968' W 124° 21.012'

- Sea Lion Gulch: N 40° 14.376' W 124° 19.887'

- Randall Creek: N 40° 12.023' W 124° 16.902'

- Gitchell Creek: N 40° 05.637' W 124° 06.114'

- Black Sands Beach: N 40° 02.772' W 124° 04.740'

Car camping near Mattole and Shelter Cove

Mattole

The BLM has a car campground at Mattole with a dozen or so sites and potable water. If this is at capacity, you can walk in and camp on the beach. You must stay at least 500 feet from the campground on the beach. No camping is allowed 1 mile inland from Mattole Beach along the Mattole River.

Shelter Cove

The best camping near Shelter Cove is at the BLM Wailaki Campground. It is located about five miles from Black Sands Beach on the Chemise Mountain Road. It has potable water, pit toilets, and spacious sites. Nearby is the Nadelos Tenting Area. This is a parking lot with an adjacent area for tent camping. It too has potable water and a pit toilet.

Tolkan Campground is another car camping option. It's a long 7 miles from Black Sands Beach on King Peak Road. There is no potable water, but it is a beautiful, spacious campground.

Note: Both of these stores are located miles inland from the Lost Coast Trail. It would be difficult to reach either one on foot.

Permits

Overnight hikers in the King Range Wilderness must reserve a permit. These are available from www.recreation.gov. Permits are not required for car campgrounds or for day hiking. The max group size per permit is 5.

The BLM allows a total of 60 overnight backpackers per day from May 15 to September 15, and 30 per day the rest of the year.

Permits for the following year are first-come-first-serve and released on October 1. Unfortunately there is no lottery system, and permits are snapped up quickly.

Camping on the Lost Coast Trail

The BLM does not restrict camping to any specific area. They do encourage backpackers to stay in obvious existing campsites to lessen human impact. Most of the major campsites on the Lost Coast Trail are tucked back from the beach in the narrow valleys carved where streams empty into the sea. Camping off the beach offers some shelter from the wind. The main camps are at Cooskie Creek, Randall Creek, Spanish Creek, Kinsey Creek, Big Creek, Big Flat, Shipman Creek, Buck Creek, Gitchell Creek, and Horse Mountain Creek. Smaller campsites dot the rest of the route.

Water

Unlike many of the other hikes in California, fresh water is plentiful along the Lost Coast Trail. Streams are at most several miles apart. All water in the backcountry needs treatment to remove harmful pathogens and contaminants. Never drink untreated water.

Water from larger streams (Flat Creek, Cooskie Creek, etc) can taste rank in the summer even through a good filter. You may appreciate filtering extra water at a smaller stream before heading into camp.

Bear Canisters

Bear canisters are required when backpacking overnight in the King Range. You need to carry one of the approved models listed on this page, and each hiker needs to carry a minimum of one can.

Black bears in the King Range will break into backpacks and tents if they smell food or scented items. You need to store all toiletries (e.g. sunscreen, toothpaste), food, dogfood, and any other scented items (e.g. surfboard wax, insect repellent) in the bear-proof can. All scented garbage needs to be stored as well.

If you do not have your own bear-proof canister, you can rent one for $5 per trip plus a $75 credit card deposit. They are available at the Arcata Field office, at the King Range NCA Project Office in Whitethorn (on the way to Shelter Cove), or from the Petrolia General Store near Mattole. The Petrolia store only accepts cash for can rentals. During peak hiking season, inventory can run low at some of these locations, so phone ahead before your trip to check.

The field office in Whitethorn has a 24 hour drop-box. Be a good lad and clean out your bear canister before dropping it off.

Each can will hold about three days of food and toiletries for one hiker. Their capacity is 600 cubic inches.

Exploring the Lost Coast Trail

An interpretive walk from Mattole Beach to Black Sands Beach (Shelter Cove)

Mattole Beach to Punta Gorda

The Lost Coast Trail begins near the mouth of the Mattole River at Mattole Beach. There are parking lots, a car campground, potable water and pit toilets here. The trail embarks from near the parking lot and leads into the dunes along the upper beach.

This area is rich in human history and has been inhabited by various peoples for at least five millennia. When European settlers arrived, they found permanent indigenous settlements up the Mattole River valley, and seasonal settlements at the mouth of the river. It appears that the inhabitants lived near Mattole Beach during the milder months of the year to hunt and gather resources. During the winter they would move inland up the river, presumably to put a few miles of land between them and the weather that blew in off the ocean.

One of the few remaining traces of the Mattole people is still visible just steps from where the Lost Coast Trail starts. The people who lived here would pile their junk -- shells and bones -- into large heaps called shell middens. You can see remnants of a shell midden behind a fence. An interpretive sign marks its location.

The first two miles of the trail winds through the dunes of American dune grass. Jack rabbits and rattlesnakes frequent the coastal prairie. This trail has long been in use in recent times. When the Coast Guard maintained the nearby Punta Gorda Light, a horse named Old Bill spent 30 years providing transport along this route. Legend describes him as mean and ornery, with an affinity for jumping over any puddle of water, no matter how small.

After about 2.5 miles the trail empties out hikers onto the beach. Rounding Punta Gorda (which may be inaccessible at high tide), the Punta Gorda Lighthouse comes into view.

The low tide reveals tide pools here and sea lions frequent the rocks. As you near the lighthouse, you must cross Fourmile Creek. It is usually only a few inches deep in the summer.

The private cabin here is impossible to miss. It is the first of several pre-1970 cabins along the route. They are owned by people who did not want to sell their property to the BLM when the King Range National Conservation Area was formed. These cabins could be the definition of "off the grid." They are rustic and battered by years of weather. The human settlement, juxtaposed with the harsh landscape hint at how difficult life must have been for early settlers along the west coast.

Just ahead lies Punta Gorda Lighthouse. You will pass by tidepools and sea lion colonies along the way.

The Punta Gorda Lighthouse

The Punta Gorda Lighthouse has more references in modern history than anywhere else along the Lost Coast. It's a wonderful place to explore and ponder, especially if you know its history.

The Punta Gorda Light was first lit in the winter of 1912. It provided a beacon a dozen or so miles south of Cape Mendocino, the westernmost point of California. Here the land sticks into the Pacific Ocean like a bony elbow. In darkness and fog, and with many offshore rock formations, it's a formidable obstacle for maritime traffic along the coast.

Before funding in 1908, the coast guard had been requesting a light at Punta Gorda for many years. Between 1899 and 1907, at least eight ships ran aground near here.

On a July night in 1907, 87 lives were lost when the passenger steamer SS Columbia collided with a lumber schooner in the fog near Punta Gorda.

The wreck of the SS Columbia had little to do with the dangers of sailing along the Lost Coast and more to do with the hazards of operating at full steam in limited visibility and without modern collision detection technology. Regardless, the location of the accident helped push the Punta Gorda lighthouse project into consideration. The next year congress approved a budget of $60,000 (about $1.4 million in 2015) to build the lighthouse.

Four years later the lighthouse was lit. The living quarters included three craftsman-style houses, a barn, blacksmith shop, and other outbuildings.

Punta Gorda Lighthouse operations

Supplying the lighthouse crew was a difficult undertaking due to the remoteness and lack of roads. Even when a road to Mattole was build in the mid 1930's, it would often wash out in winter rains. The caretakers were cutoff from the rest of the world. With only Old Bill the horse to help haul supplies, Punta Gorda was not a desirable assignment.

The Coast Guard kept Punta Gorda Lighthouse operational from 1912 to 1951. During World War II, the Coast Guardsmen patrolled the beaches from here to Shelter Cove. During this time, fear of Japanese invasion of the West Coast grew in the minds of Americans.

By 1951, better navigational methods made maritime travel up the coast safer. The Punta Gorda Lighthouse was decommissioned and transferred to the care of the Bureau of Land Management.

In the late 1960's this served as a minor hippy commune after long-haired squatters moved into the abandoned houses. After repeat evictions, the BLM burned all the wooden structures to the ground. Only the lighthouse and oil house remained. The site made the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Today the Punta Gorda Lighthouse is a popular lunch spot for hikers. It is only 27 feet in height, and you can climb the spiral iron staircase to where a bivalve Fresnel lens once stood. It rotated at twice per minute, sweeping one of its dual beams across a passing ship every fifteen seconds.

Punta Gorda to Cooskie Creek

Leaving the Punta Gorda Lighthouse behind, you pass by the foundations where the crew quarters once stood. The trail climbs away from the shore, offering easier travel. Below on the rocks you can spot a few mangled pieces of ships. The rusted remains of an oil tank sits near the lighthouse and is from the 1905 wreck of the St. Paul. The St. Paul was 15 miles off-course in heavy fog when it ran aground here. A passing tugboat managed to save all 65 people on board.

For the next mile firm trail skirts the grassy slopes above the beach. Gulls and terns are abundant, their favorite roosts painted white by layers of uric acid. Peregrine falcons cruise the updrafts and keep a watchful eye for unwitting smaller birds. Turnstones inspect the rocky shoreline. Ravens, usually looking like they're up to no good, keep a watchful eye on hikers as they pass. Further down the cliffs, wakes of turkey vultures dispatch with anything dead that washes up along the shore.

Alongside the trail small sparrows and occasional goldfinch flutter and crash about the brambles. Western fence lizards scurry away from sunny patches of rock as you pass. Coast garter snakes meander along the rocky slopes.

Approaching Sea Lion Gulch, the cliffs become too steep for the trail to continue. The trail descends through some tent sites perched high on the bluff and follows the creek ravine down to the beach. This marks the beginning of four miles of the trail that is impassible at high tide. Make sure you've done your homework on the tides before continuing. In several places the cliffs are steep, and there would be no way to escape a surging tide. Within this impassible section, camping is available at Cooskie Creek, about 2 miles ahead.

At Sea Lion Gulch, sea lions hunt among the kelp and argue over prime sunning rocks. They are wary of hikers, and you might have an audience of inquisitive heads bobbing in the surf as you pass. The rocky shoreline soon gives way to a sandy beach.

The beach comes to a dead end against an impassible point just beyond a small creek. A unique rock perched against the sky on a large boulder marks the location. Even at low tide, it is unsafe to navigate around this point along the shore. It is too low and the currents are dangerous. Look for a wooden sign marked "LCT" just above the creek.

The trail climbs up above the beach offering one last view of Sea Lion Gulch. Over the rise the ruins of a cabin come into view, battered and shattered by years of storms and neglect. A single agave cactus grows in the yard, and a patch of torch lilies bloom nearby. Just past this point a sign marks the start of the Cooskie Spur trail, which makes a 1.2 mile ascent to the Cooskie Creek trail.

Continue through the creek bed and over the next hill. When you come to the next creek bed a short distance later, the trail forks, with one branch leading to the beach. The other path climbs the hillside here, but this leads only to an overlook a quarter mile away. One might surmise that this way-trail is stomped out by hikers hopeful to make it to Cooskie Creek at high tide. Crumbling cliffs, carved by landslides chop the path from the hillside. The nerve-racking heights of this vantage mark the end of the line, and you'll need to backtrack.

Descending to the beach, the next several miles miles are challenging. The beach is a narrow strip of football-sized rocks that roll and shift underfoot. The waves pin the hiker next to the crumbling towers of the sedimentary cliffs. Here, erosion is a constant process and landslides are frequent. Watch for falling rocks.

Cooskie Creek, a steep green notch in the slope, is visible ahead. It offers many spacious camp sites along the creek and is sometimes crowded on weekends. Midweek, you may have the entire place to yourself. In the summer you can spot salmon and trout fry as they dart along the creek bed.

High tide cuts Cooskie Creek campground off from Lost Coast Trail access on both sides. Watching the waves pound against the cliffs offers a remarkable sense of isolation. It is perhaps the best taste of solitude the Lost Coast Trail can offer.

Cooskie Creek to Big Flat

The trail from Cooskie Creek to Randall Creek isn't so much a trail as it is a beach that emerges twice a day at low tide. Exercise caution along this stretch as there are many points where there is no place to escape a sudden wave. Furthermore, there are frequent landslides in this area, and small rock avalanches are common. Keep an eye out for large waves as well as falling rocks from above.

Here the landscape is raw and savage. Tidal surges undercut the gravel and clay cliffs, which look like they could collapse at any moment. Cormorants roosting among the cliffs are some of the only signs of life here. Outcrops of crumpled ribbon chert protrude from clay and muddy sandstone.

Comparisons of satellite photographs from 2005 and 2006 show that major landslides occurred along this stretch of beach during the interim. That winter saw a massive low pressure system stall over the area, breaking 24 hour rainfall records at many measuring stations. The saturated hillsides tore loose and slipped down into the sea.

Walking along this stretch of beach, you can see where large sections of hillside broke loose and slid into the sea. Huge expanses of hillside lay bare, and few patches of grass have yet to take hold. Loose rock and soil continue to crumble and wash onto the beach. You do not have to stand here long to spot rockfalls. Suffice to say, this is not the place to enjoy trail mix and a nap.

The beach finally opens up as you approach Randall Creek. This is a popular camping location, as it's about a day's walk from Matolle Beach. This is the northern tip of Spanish Flat, a wide marine terrace and pristine coastal prairie. The walk is easy and the views are expansive as you head south.

Just over a mile south of Randall Creek the Spanish Ridge Trail begins a steep climb of Spanish Hill, over 2,000 feet above. There is no water along this trail, but the side trip is worthwhile if you don't mind the workout, and want to see the Lost Coast from above.

Passing the Spanish Ridge Trail, you approach a simple private cabin. From here the trail runs parallel to a private access road. Small streams cross the prairie at regular intervals, offering clean tasting water. At low tide, you can hike along the beach here, but most people prefer taking the trail above.

After another mile and a half, the Kinsey Ridge trail branches away to the east, followed by the gorgeous Kinsey Creek. Just beyond, you can see where a large burn swept over the hillside from the flat to the ridge line of Hadley Peak at 3,010 feet. The fire did not extend beyond the ridge lines, but spread along the prairie. Now the forest of dead snags teams with new growth. Untouched by the fire, another private land owner claims the southern part of Spanish Flat. Signs attempt to repel backpackers away from the cabin and down toward the beach.

Beyond Big Creek, the marine terrace narrows in the shadow of Shubrick Peak (2,797 feet) and the trail returns to the beach. Patches of Douglas-fir grow alongside stands of burnt trees. There seems to be no obvious reason how the fire chose its path. Rounding the flank of Shubrick peak, the trail climbs to a vantage above Big Flat.

Here you can follow the private access road or the beach. The actual Lost Coast Trail meanders among drifts of sand midway between. Big Flat is home to a large resident deer population as well as jackrabbits, gray foxes, bobcats, black bears and many other species. It is a wildlife photographer's paradise.

Just three miles to the east, King Peak towers out of the ocean at 4,088 feet. This is one of the most dramatic rises along the west coast below British Columbia.

Big Flat is a popular destination along the Lost Coast Trail. It was formed in part by the sedimentary conveyor belt of Flat Creek which carries countless tons of eroded soil from the mountains to the sea. This sediment has built up gentler slope offshore, resulting in a long break. Surfers carry their boards in from Black Sands Beach to spend a few days here. In the summer the break here is often too flat to surf, but given the right conditions offshore (more common in fall and winter) a worthwhile swell can build.

The camping at Big Flat is spacious with campsites spread out at generous intervals. Deer, tamed by years of exposure to docile backpackers, wander past campsites to drink from Flat Creek.

Like other coastal streams, Flat Creek is important habitat for coho and chinook salmon, as well as steelhead trout. Salmon and steelhead are born in these streams where they live for a year before migrating to sea. As mature adults, they return to their native streams to spawn.

The drought of 2012-2015 has pushed these populations to critical levels. The winter rains are rarely enough to breach the sandbars that block the entrance to streams. In the winter of 2014, many streams in Northern California did not see salmon return to spawn. With higher rainfall than other parts of the coast, the streams along the Lost Coast have fared somewhat better. Their habitat is vital to the survival of regional salmon and steelhead populations.

The Rattlesnake Ridge trail branches from the Lost Coast Trail near Flat Creek.

Miller Flat to Black Sands Beach

On the south side of Flat Creek, Big Flat becomes Miller Flat. This is in the shadow of Miller Ridge, which leads to King Peak, just a few miles inland. Continuing south from Miller Flat, the next 4.5 miles of trail is impassible at high tide. You have no hope in getting through when the tide is above the 3 foot line, and in a few places, you'll need it to be a bit lower. Within this stretch, both Shipman Creek and Buck Creek offer camping in case you need to wait out the tide.

Leaving the gentler landscape of Miller Flat, this section of the Lost Coast Trail is severe and raw. The faces of the mountains extend straight from the sea. The beach is but a narrow shelf along the cliffs. Footing is difficult, and the going can be arduous.

This is the second major section of the Lost Coast Trail that can only be passed at low tide. Within this stretch of coast Shipman Creek and Buck Creek offer camping and fresh water.

As you're pinned against the cliffs, dodging waves and the occasional rock-fall, remember this: Just south of Shipman Creek, the ocean plunges into sudden depths of a channel of the Delgada Submarine Canyon. It gets deeper faster than almost anywhere else on the West Coast.

This canyon is a massive chute for sediment as it flows down into the deep sea. It is a remnant of the San Francisco Bay drainage. As the Pacific and North American plate slide past each other, it has migrated north at a few centimeters per year.

1.4 miles south of Shipman Creek the Buck Creek Trail branches off to climb Saddle Mtn, 3,292 feet above. The first mile of this trail climbs approximately 2,000 feet, boasting one of the steepest grades of any California Trail. This is the place to go if you want a good glute workout.

As the trail approaches Gitchell Creek, the beach opens up, and is wide enough for high tide travel. Forests of Douglas fir drape over the hillsides and down to the beach. Though the dangers of the ocean are largely behind, the deep sand and gravel slows every step. Driftwood is abundant, and shorebird density increases as the beach widens.

Surf fisherman are a sign that you are approaching Black Sands Beach. Black Sands Beach marks the end of the northern section of the Lost Coast Trail.

Where to go from here

For most people, Black Sands Beach will be the end of the Lost Coast Trail. Food and beverages are available from the Shelter Cove general store, and there is nearby car camping.

For hikers wishing to visit Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, it's possible to take the southern portion of the Lost Coast Trail. Dogs are not allowed in the state park. The trail begins a long 3.5 miles away over the ridge from Black Sands Beach. From Black Sands beach, take Beach Road to Shelver Cove Road, and stay on this until you reach Chemise Mountain Road. The shoulder is narrow and idiot drivers frequent Shelter Cove Road, so be careful. The trailhead is found 0.2 miles up the Chemise Mountain Road, and the trail is also accessible from the nearby Nadelos and Wailaki campgrounds.

Minimizing your impact on the Lost Coast

The Lost Coast Trail is a popular route. Over ten thousands visitors come here to hike each year. Maintaining a small footprint is crucial to keeping this place pristine.

Don’t feed the bearsYou must store all food and scented items in an approved bear canister. The BLM rents these for $5 per trip at several field offices.

Don’t introduce invasive speciesInvasive species devastate natural ecosystems. The Lost Coast has one of the only primordial ecosystems left on the California Coast. The invasive European beachgrass dominating the West Coast has yet to appear here. You can help protect this by cleaning your boots and gear before hiking here. Otherwise you could be spreading plant species from your last backpacking trip.

Nobody wants to encounter your poop (except my dog)The best way to dispose of human waste 6-8 inches in the wet sand, below the high tide line. On inland trails, you must bury your waste at least 200 feet from streams, camps and trails. You must pack out toilet paper.

Nobody wants to drink fecal bacteria in their water. Furthermore, it’s a horror to breach the shallow grave of someone’s poop crime in a tent site. Please be considerate to your fellow hikers and follow the above guidelines.

Wash dishes in the intertidal zoneThe coastal streams provide habitat for many species including endangered salmon and steelhead. Land animals, including hikers like yourself, rely on these streams for drinking water. Dish washing and any soap use should stay 200 feet from streams. You can also do this in the intertidal zone.

Pack out your trash, bury food scraps in the oceanPack out toilet paper and all trash with you. Burning and littering has a negative impact on wildlife and visitors. Dumping food scraps around campsites attracts rodents, which in turn attract rattlesnakes.

Don’t let Smoky the Bear downWhile the King Range gets a lot of precipitation in the fall and winter, wildfires pose a risk in the dry season. Camp fires are often prohibited between late spring and fall. Check for notices posted at trailheads if you want to have a campfire.

If campfires are not banned and you choose to have one, don’t leave it unattended. Completely extinguish the fire before leaving. Coals should be cool to the touch.

Be considerate to othersMost people come out here seeking some degree of solace. Please by respectful to others by keeping noise to a minimum, especially around camps. It’s good backpacking etiquette to camp out of sight from others when possible.

Hazards and staying safe along the Lost Coast Trail

Sneaker waves

Sometimes Lost Cost visitors get swept out to sea. Signs at Shelter Cove and Mattole remind hikers to “never turn your back on the sea.” This section of coast is fully exposed to the open ocean and conditions can change rapidly, and large waves (dubbed "sneaker waves") sometimes spring out of a calm sea. In Northern California the ocean gets deep fast. There are no offshore reefs or long, shallow beaches to temper incoming waves.

The steepness of the beaches creates a powerful undertow. Rip currents are common. The water is cold, and without a wetsuit, muscles will stop responding within minutes. Survival odds grow dismal after about twenty minutes in the water.

As you hike the Lost Coast Trail, it’s a good habit to keep an eye out for the best escape route if faced with sudden waves. Keep another eye on the bluffs above for falling rocks.

Wave patterns are often chaotic. It’s not unusual to see a set of formidable waves spring from a gentle sea with little warning. These are commonly referred to as sneaker waves. Many sections of the Lost Coast Trail are through tight gaps between cliffs and the sea. Here the hiker would be most vulnerable if surprised by a large wave.

Wind exposure

With the beach exposed to thousands of miles of open ocean, wind can be strong along the Lost Coast Trail. Camp in one of the major camps where the hills offer some shelter from the wind. Secure your tent well.

Rattlesnakes

Northern Pacific rattlesnakes are found along the Lost Coast and throughout Northern California. They will retreat if given the space, but may strike if they feel threatened. Usually this happens when they are surprised or provoked. Along the Lost Coast, they will often crawl alongside driftwood where they have protection along one side. This poses a danger to hikers and dogs who may surprise a snake by stepping over a log and directly into the snake’s strike radius. Watch for snakes around driftwood. Also use care when walking through tall grass or brush, places where rattlesnakes hide during the day. Discourage your dog from running around piles of driftwood or crashing through brush.

Ticks

Ticks are abundant along the Lost Coast and many carry and transmit Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium responsible for Lyme disease.  Lyme disease is a serious disease, and Humboldt County has the second highest incidence rate in California. Wear long sleeves and pants. Ticks are easier to spot against light colored clothing. Consider using tick repellents such as DEET or permethrin. Perform tick checks often by examining exposed skin and clothing. Ticks are often overlooked on the scalp or behind an ear. Examine your sleeping bag every morning for ticks that may have fed and detached.

Lyme disease is a serious disease, and Humboldt County has the second highest incidence rate in California. Wear long sleeves and pants. Ticks are easier to spot against light colored clothing. Consider using tick repellents such as DEET or permethrin. Perform tick checks often by examining exposed skin and clothing. Ticks are often overlooked on the scalp or behind an ear. Examine your sleeping bag every morning for ticks that may have fed and detached.

If you are bitten by a tick, remove it immediately. Transmission of harmful bacteria can take many hours.

How to remove a tick

- Grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible with a pair of tweezers. If you don’t have tweezers available, use your fingers protected with tissue paper.

- Pull slowly and steadily straight out, being careful not to jerk, twist or crush the tick. You don't want to squeeze or crush the tick, as this can inject infectious fluids from the tick into the bite wound.

- Remove any tick mouth parts that break off in the wound.

- Wash the wound with generous amounts of soap and water, and apply a mild antiseptic if available.

- Consult your physician as soon as possible. Common antibiotics can often cure Lyme disease if given within the first few weeks of an infection.

Poison Oak

Poison oak is abundant along the Lost Coast. Learn to recognize it so you can avoid it. The rashes from poison oak can be agonizing and severe. Wear long pants and closed-toe boots when hiking the Lost Coast Trail.

Avoid touching your dog (“the poison oak fairy”) and give it a good bath as soon as your hike is over.

If your skin gets exposed to poison oak, wash with an abundance of soap and water as soon as possible. The same goes for any clothing or gear that brushes up against the plant

If the oil from the plant rubs off on something else, it stays toxic for years. Wash any gear that could have touched poison oak (hiking poles, etc) when finished with your hike to avoid surprise rashes later.

In more depth

Geology of the Lost Coast

Earthquake country

The King Range is a great crumbling mass of sediment that thrusts from the Pacific Ocean to a height of 4,088 feet just a few miles inland. The King Range is a small and steep mountain range formed near where three tectonic plates meet. Named the Mendocino Triple Junction, this place has complicated and violent geology. Here the Pacific Plate, the North American Plate, and the Juan de Fuca Plate come together.

This is also the terminus of the San Andreas fault. From here the fault runs toward San Jose. It marks the boundary between the Pacific plate and the North American plate.

Earthquakes are frequent. In the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the fault ruptured from this terminus to San Jose. Thousands of landslides occurred around Shelter Cove. Some buried beaches as hillsides spilled into the sea. In 1992, a smaller quake uplifted marine terraces as much as three feet near the Lost Coast.

The mountains of the King Range have been building since the Cretaceous period. Driven by tremendous tectonic forces, sedimentary layers compress and push skyward. In some places intense pressure deformed the sediment into metasedimentary rocks. Fighting constant erosion, the buoyant crust has risen to King Peak at 4,091 feet.

Weather on the Lost Coast

It is not just tectonic activity that leaves its mark on the King Range. Erosion is at constant work here. An average of 100 inches of rain falls on the King Range each year. During El Niño years, the rainfall can be twice this figure.

In the winter and spring a semipermanent low pressure system, called the Aleutian Low develops over the Gulf of Alaska. The weather system flows counter-clockwise sending storms and rainfall to the Pacific Northwest and Northern California. As the westerly winds are forced over the King Range, the air cools to the condensation point causing clouds and rain to form. This makes the King Range one of the wettest places in the United States. Most of the rainfall occurs between October and May. June through September are usually dry and mild, but still see the occasional storm.

When moisture saturates the soil, hillsides can crumble into the grips of the undertow. When high tides and storms combine, the waves can rip trees from their roots. Sometimes storm surges can even drive whales over sandbars of coastal streams, leaving them trapped when the tide recedes.

On a still summer's day with gentle waves lapping at the rocks, it can be hard to imagine the intensity of the storms here. You needn't look far for clues though.

Recent history

For the Lost Coast, it seems likely that desolation influenced its name. The name "Lost Coast" emerged in print as a declining lumber industry drove an exodus of settlers in the 1930’s. Not much has changed here over the decades.

The hilly landscape and weather combine to make the building and maintenance of roads difficult. It's a long, winding drive from here to Highway 101, and not many reasons to make it. It's an area popular with off-the-grid types -- hippy transplants from the Bay Area, modern homesteaders, marijuana farmers, hunting and fishing guides. There's not much to say about modern inhabitants except that they're self-sufficient and compete heavily with Mexico to keep a lot of pupils dilated. It is probably the only place in the country where you'll see someone with dreadlocks driving a lifted Chevy truck with a gun rack in the back window.

Pre-European History

Looking back to pre-European history, we find that this area has been inhabited by humans for millennia. The Mattole river valley is rich in archaeological history. There is evidence of human settlement dating back 5,000 years.

What we know of the Mattole people we largely deduce from the unique geology of this region. Mattole Beach is a sea terrace undergoing uplift from the Mendocino Triple Junction. The land averages an impressive 13 feet of uplift every 1,000 years. The M7.2 1992 Petrolia earthquake raised this stretch of coast by over 3 feet.

As a result of the uplifting, evidence of beachside settlements get pushed up the beach with time and preserved.

The mouth of the Mattole river was a source of seasonal resources. People lived in temporary structures of driftwood and animal hide. They gathered shellfish and seaweed, fished for salmon and surf smelt, and hunted seals and sea lions. They wintered in nearby settlements further up the Mattole river.

Pacific Coast Athapaskan natives influenced the late culture and dialect of the Mattole people.

Last of the Mattole

We know little of the Mattole people, except that they met a violent and tragic end at the hands of European settlers. The Mattole people were nearly wiped from the earth after European settlers arrived.

At the Eureka library, microfilms of early Humboldt Times partly document how this happened: White settlers came to the Mattole area to raise cattle. They named the area New Jerusalem. Initial contact with the Mattole people was friendly, but peace was short-lived.

In the mid-19th century conflicts emerged between the white settlers and the Mattole people. There were murders on both sides. By 1858, conflicts were frequent enough that a peace treaty was established, but it did little to quell the violence.

Between 1858 and 1864 a series of disputes with settlers escalated into massacre of most of the Mattole at the hands of local militias and the army. Many of the natives that weren't killed in fighting were sent to a prison camp in Humboldt Bay.

In 1868 a measles epidemic wiped out almost all remaining Mattole living in the region. Only a few descendants survived. They were mostly children. They grew up with only thin threads of experience in their native culture. The Mattole language went silent in the 1930's, slipping into extinction. There was almost nothing recorded of Mattole culture. Written history mentions little more than how many were killed on what date.

Additional Resources

- The Lost Coast Trail Tides Planner

My interactive tides planner for finding intertidal zone hiking windows by date based on Shelter Cove's predicted tides by NOAA. - Shelter Cove Tides and Currents (NOAA)

Double-check your Lost Coast Trail hiking plans with the latest tide data from NOAA. - Quick Guide to Hiking California's Lost Coast (PDF download)

A useful and entertaining no-nonsense guide to the Lost Coast Trail in a printable 1-page PDF format by the folks at SierraSoul.com. - King Range National Conservation Area (official website)

The latest information for the King Range by the Bureau of Land Management. Check this for trail or park alerts, rules and regulations.

Questions? Trip reports? Suggestions?

How did your trip go? Did you find this article helpful or do you have something to add? I'd love to hear from you. Feel free to comment below or send me a message.